This post summarises the current position on grants and loans for full-time students in higher education in Scotland, and the background to it.

Background

(i) Fees and other payments

The Scottish Government funds the whole tuition cost for almost all first-time, full-time Scottish and EU students in Scotland, from the government’s cash budget. Therefore no-one from any background has to borrow for part or all of their fees. Scottish students will only need a fee loan (as students in other parts of the UK get, to defer fee payments) if they go to study elsewhere in the UK.

Between 2001 and 2006, young students entering degree-level HE full-time were liable to pay the graduate endowment, a single payment of £2,000 at 2001-01 prices, after finishing university. The income from the GE was in theory ring-fenced for student bursaries. Graduates could either pay it in cash or add the liability to their existing student loan (or take out a first-ever loan) to defer the payment. Because of exemptions for HNC/D students, including those on “2+2” models, mature students, disabled students and single parents, slightly under half of all the full-time students the SG supported were liable to pay the GE, which was bringing in around £23m p.a. by 2007 (more here). When the current Scottish Government says it brought in free tuition, it is referring to its abolition of the endowment in 2007. It is also often, in practice, describing its decision not to use devolved powers to copy either of the fee regimes which have applied in England since 2007.

(ii) Living cost grants

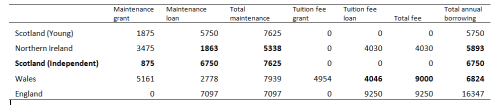

Scotland has relatively low student maintenance grants (here called bursaries). Most living cost support is offered instead as student loan.

Between 2010 and 2012 inclusive, the means-tested grant for younger students, Young Student Bursary, was frozen in cash terms (see here for more on how its value changed from 2001 onwards). In 2013, the Scottish Government cut its total spending on maintenance grants by around £35m, or one-third. The maximum YSB was reduced from £2,640 to £1,750, and it was withdrawn more quickly as income rose. The government lowered the income at which maximum YSB was payable from £19,300 to £16,999. Many students lost £900 a year and some much more. The Scottish Government argued they could make up the difference by borrowing to fill the gap. Older students get the lower-rate Independent Student Bursary. This was introduced as a lower-rate grant by the Scottish Government in 2010, and then also scaled back in 2013.

In 2015, the Scottish Government added £125 back on to some grants, costing it around £5m, and in 2016 it reversed most of the cut to the threshold for maximum grant, raising it to £18,999 (likely to have cost it a bit under £2m a year).

The current system

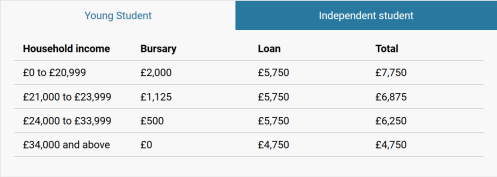

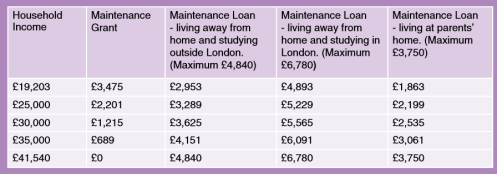

The resulting living cost model in 2016-17 is in the table below.

| Young | Independent (ie mature) | |||

| Bursary | Loan | Bursary | Loan | |

| 0-18,999 | 1,875 | 5,750 | 875 | 6,750 |

| 19,000-23,999 | 1,125 | 5,750 | – | 6,750 |

| 24,000-33,9999 | 500 | 5,750 | – | 6,250 |

| 34,000 plus | – | 4,750 | – | 4,750 |

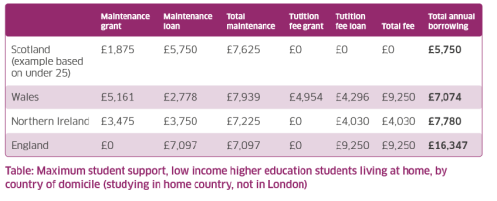

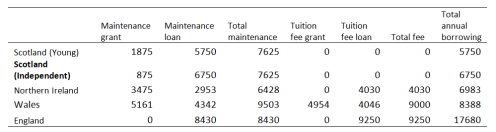

A particular feature of this model is that it is built round those from the lowest incomes, especially mature students, taking out the highest loans. Until grants were abolished in England in 2016, Scotland was the only part of the UK taking this approach. It means that someone at a low income who wishes to take out their full entitlement to living cost support over four years faces a debt of £23,000 plus interest if they are younger, and £27,000 plus interest if they are older. Grants are higher in Wales and Northern Ireland (where students also only have to borrow for the first £3,900 of their fees: true for Welsh students anywhere in the UK, for NI ones in NI).

Actual borrowing

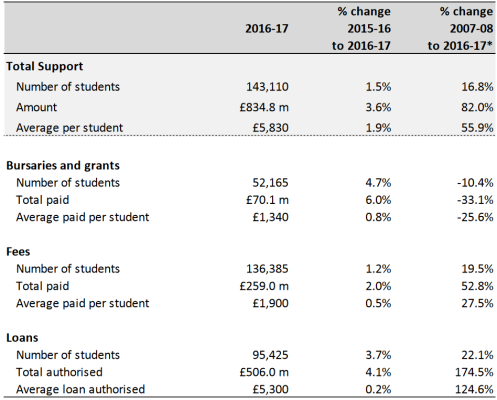

Figures on annual borrowing by income are published annually by the Student Awards Agency Scotland (SAAS). The latest are here (see Table A6). They show that Scottish students borrowed a total of £0.5bn in 2015-16.

Around 70% of Scottish students take out a loan in any given year, and almost all those who borrow, borrow the whole amount they can.

The table below is adapted from the official statistics. I’ve added two columns. One shows average borrowing across the group as a whole, i.e. including borrowers and non-borrowers. The other shows the percentage who don’t borrow in each income group. It’s reasonable to assume from other research that there are more non-borrowers in the higher income group because students’ access to family resources tends to rise as family income increases. It is likely that even within this group, non-borrowers are more prevalent at higher incomes: it is quite plausible that at, say £60,000+, non-borrowers are in the majority.

The net effect of lower income students having higher loan amounts and making more use of loans is that students in the highest income range borrowed in practice around half as much per head (around £3,000) as those in the lowest income band (over £6,000). Another way to look at this is that Groups 1 to 4 below accounted for only 43% of all students, but took out 54% of all debt.

Borrowing by income band 2015-16

| Total students | Borrowers | Average borrowing (active borrowers) | Average borrowing (all) | % Non-borrowers | ||

| 1 | No income details: receiving max bursary | 10,055 | 9,360 | 6,660 | 6,201 | 7% |

| 2 | Up to £16,999 | 23,895 | 19,105 | 5,890 | 4,711 | 20% |

| 3 | £17,000 to £23,999 | 8,955 | 7,220 | 5,760 | 4,648 | 19% |

| 4 | £24,000 to £33,999 | 8,980 | 7,265 | 5,610 | 4,542 | 19% |

| 5 | £34,000 and above | 2,965 | 1,850 | 4,650 | 2,901 | 38% |

| 6 | No income details: receiving no bursary | 70,010 | 46,830 | 4,650 | 3,112 | 33% |

Note: I’ve removed EU students (14,705) from the figure for total students, as these students can’t borrow. I have assumed that they were contained in Group 6, as very few can claim means-tested support. That may not be exactly right, but it should be near enough. Most students with an income over £34,000 will be in Group 6, which covers those who chose not to submit income details, generally because they are above the threshold for bursary. Group 1 by contrast will be those who had no relevant income to declare and got the highest bursary level. Group 5 is a small group whose income details SAAS knows, although they are over the bursary threshold. I have excluded here a very small group of low-income students separately shown in the SAAS table who anomalously have no income but don’t get full bursary: there’s something odd going on with this group (it may be that many don’t complete a full year).

Caution: final borrowing

Separate figures are published each year for students’ final borrowing. The most recent Scottish figure is £10,500. These figures are widely quoted but have to be handled with care. The average will be brought down by the large number of students in Scotland on one or two year courses, and – as shown above – any average will conceal variation by income. More on that here.

Conclusion

The Scottish system is not debt-free in the absence of fees: indeed Scottish students are borrowing a substantial amount as a group each year. The Scottish approach relies heavily on loans to cover the state’s role in providing low-income students, in particular, with living cost support. Grants are now so low that those from the lowest incomes are taking on the most of that living cost debt. Equally, at high incomes, many students will be borrowing nothing.

Defending existing policy in Scotland means defending this outcome.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

It seems common to assume that we’re faced with a straight choice on tuition fees, where the state either funds the whole of everyone’s tuition costs, or all students have to take out a loan for £9,250 a year. It’s a perspective stuck in a binary choice between whatever-we-do-now-in-Scotland and whatever-they-do-now-in-England. Other options are of course available. That’s what this post is about.

A starting point

The simplest alternatives for fees are:

- setting the fee level at some number more than zero, but less than £9,250;

- means-testing fees; or

- some combination of these two.

There’s a fairly common argument that any move away from free tuition inevitably means Scotland would end up where England is: the slippery slope perspective. That puzzles me, because we would only end up there if that was what the politicians we elected chose. It seems to assume we can trust them to keep it free, but not to maintain any alternative position. On this thinking, tuition fees are an addictive drug, from which governments must be kept away at all costs. I’ll come back to that at the end.

If you reject this straitjacket, and believe that the Scottish political system is capable of managing other things, what might the alternatives be, and what would they mean for students?

Note: I’m not advocating a specific model here, but demonstrating one different way things could work, as a starting point for a less constrained debate. There are more radical ideas out there (here’s one), involving more fundamental change. All I want to show is the space for alternative outcomes, just within the current broad general approach.

Living cost support matters

There’s no point designing a student funding system which only looks at one part of the story.

If you are only interested in thinking about fees in isolation, and don’t care much about living cost support, especially for low-income students, then look away now. You and I are never going to have a mutually rewarding conversation about this.

A lot of people in Scotland at this point suggest that living costs are a secondary (or even non-) issue, because students can always live with their parents and/or work their way through. I disagree for the reasons set out in Footnote 1.

The modelling below assumes decisions on living costs are as important as fees, should be interlinked, and looks at combined effects.

Fees: upfront or deferred?

Even the most vigorously ideological advocates of tuition fees recognise that students tend not to have money at the moment. It is very rare to find anyone, not even Milton Friedman, advocating unassisted upfront charges (Footnote 2 describes the UK government’s short experiment with this).

Thus, in no part of the UK do first-time students now have to find the cost of their fees from their or their families’ existing resources. With a few exceptions in Scotland and elsewhere, higher education is free at the point of entry for all first-time undergraduate students in the UK, because at minimum they can take out a government-subsidised student loan to defer the full cost of their fees until they are earning above a certain level.

It’s hard to over-stress this point for readers in Scotland, where it still seems to be widely believed that students in England have had no choice but to find £9,000 a year from their families. Had that been the case, the system there would simply have collapsed. It is precisely because fee costs are deferred that debt is so high in England.

So the model assumes that any fee is matched £ for £ by a government subsidised loan and that, as in other UK systems, the fee loan (a) would be repayable contingent on earnings, in the same way as maintenance borrowing is now, and (b) is added to any maintenance loan to form a single debt, so that no-one is paying off two loans in parallel.

Debt aversion

Regardless of any evidence from England (Footnote 3), it is possible that debt aversion should be a major concern for Scottish policy makers. In that case, however, we should already be worrying.

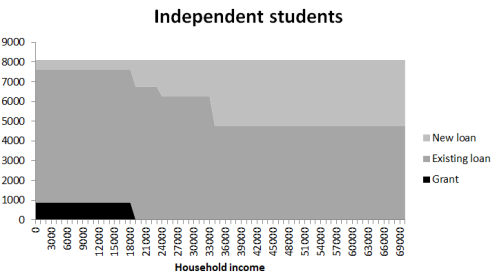

Living cost support for low-income Scottish students is now provided largely through loans, because grants are relatively low. Here’s the figures for support from the Student Awards Agency Scotland (SAAS) for 2016-17.

| Young student | Independent student | |||

| Household income | Bursary | Loan | Bursary | Loan |

| £0 to £18,999 | £1,875 | £5,750 | £875 | £6,750 |

| £19,000 to £23,999 | £1,125 | £5,750 | £0 | £6,750 |

| £24,000 to £33,999 | £500 | £5,750 | £0 | £6,250 |

| £34,000 and above | £0 | £4,750 | £0 | £4,750 |

The model below illustrates how in a system which includes some fee-paying, low-income students can still have less debt than in one with free tuition, while protecting the value of their total living cost support.

The scale of student debt in Scotland and its distribution

Around £500 million is now borrowed each year by Scottish students. At the moment, annual borrowing is skewed towards those from lower-income households, for two reasons:

- they borrow more on average, and

- they are more likely to make use of student loans.

As a result, over half of all student loan is taken out each year by students declaring a household income below £34,000, although fewer than half of students fall into that group.

The current statistics don’t allow us to differentiate amongst those with incomes over £34,000. But looking at earlier data, there’s a good chance that there’s a similar skewing of debt within the higher income group, towards middle-income households and away from the highest income ones.

The model removes the current built-in assumption that the highest debts should be taken on by those from the lowest incomes, again while protecting current total spending.

What could be different?

Put simply, we could move the debt around, so that more of this £500 million is taken out by students from higher-income backgrounds, and less by those from lower-income ones.

That means finding more to spend on grant, by spending less on fee subsidies, and expecting those at higher incomes to borrow some of their fee cost.

Mechanisms

There are in essence three ways to get this effect.

- Means-test the fee.

- Apply the fee to everyone, but then have a separate means-tested fee grant which immediately wipes it out for lower-income students.

- Apply the fee to everyone, but then build a means-tested off-setting amount into the living cost grant, before making any other increases.

Different mechanisms would have different implications for practical administration, public understanding/presentation, student behaviour and the detail of public finances. But they would all provide an identical boost to the amount of grant provided at lower incomes for the same level of fee.

One basic model

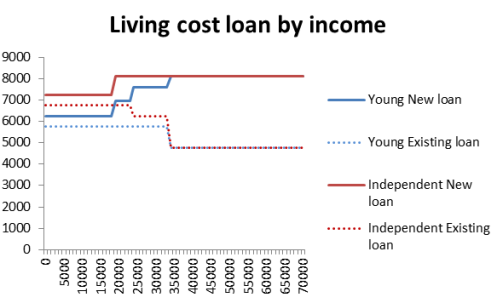

The model below asks students from the highest income households to borrow one half of the average cost of a university place in Scotland. So students from these households would be offered a government-subsidised fee loan to cover a fee of £3,500 a year. The cash released from tuition fee subsidies would be put back into grants.

How much would a £3,500 fee raise?

SAAS currently supports around 140,000 students, of whom around 15,000 are from the EU. I’ll concentrate for now on moving the public subsidy around between the 125,000 Scottish students. A separate section below considers EU students.

If Scottish students from the highest quarter of student-providing households by income were liable for the fee, it would notionally release around £110m a year from tuition fee subsidies (125,000 x 25% x £3,500).

I can’t say what the income cut-off would be, because the Scottish data on students is now too aggregate to show that. Looking at figures for years before 2013, when more detail was provided, I’d guess it would be somewhere between £50,000 and £60,000 of household income (around the highest 15-20% of all households in Scotland by income, after equivalising for a family of 2 adults and 2 children).

How could the money saved on fee subsidies at high incomes be used to bring down debt at lower incomes?

I’ll spend the money on substantially increasing means-tested maintenance grants, on which we now spend only £55m a year.

It would cost c£30m to switch £1,000 of living cost support from loan to grant for those on the Young Student Bursary.

I’ll spend a further c£40m on giving independent students (for example, those over 25, or who are parents, or married/in a partnership) the same bursary as young ones, and bringing down their debt, because these students in Scotland are on a much less generous grant and a higher loan, and there’s really no good way to justify that.

I’ll also spend c£15m on a new £1,000 grant for students from households between £34,000 and £45,000, because these families, who are not awash with cash, are expected to find much more out of pocket help for their children in Scotland than is the case in the rest of the UK and that’s a concern: more here.

The net annual effect on individual students at different incomes would be:

- Young students with incomes below £34,000 would gain £1000 in grant and lose £1000 in debt, with no change in the total value of their living cost support.

- Those with incomes between £34,000 and £45,000 would gain £1,000 in grant and therefore £1,000 in total living cost support, with no change in debt.

- Nothing would change for those between £45,000 and the fee liability point.

- Those liable for fees would have £3,500 more debt a year and no change to living cost support.

- For mature students it’s a similar picture, except that they would gain more grant and lose more debt.

Using this approach, all students are now offered the same living cost loan (£4,750), with cash grant used to do any additional income-based targeting

I’ve spent approaching £90m. I assume that due to things I’ve failed to take into account, income wouldn’t be as high and expenditure would be higher, so my spending plans may still be a bit ambitious on this level of fee. But they will be in the right general area. If students from the wealthiest quarter of households were expected to borrow £3,500 a year of their tuition cost, it seems likely that we could nearly treble our spending on maintenance grants.

The effect on the new fee payers

Total debt for those at high incomes would come to a maximum of £8,250 a year. Two points about that. First, in practice many of these students would only have a £3,500 annual debt, because living cost debt take-up is lower in this group, presumably because many have all their living costs met by their parents.

But the second is the more important. Low income mature students are already expected to incur £6,750 in living cost debt – and most do. If you have managed in recent years not to be outraged at the reality of a £6,750 annual debt for most mature students with no income, you are not in strong position to be outraged now at a theoretical maximum debt of £8,250 a year for students from high income families which many won’t actually incur.

Is this a good model?

This would be a pretty clunky way to do things. The Scottish system already incorporates large step changes in entitlement, and it’s not an ideal approach. However, because the data comes packaged that way, it’s hard to model anything without copying that.

The point of this model is not to advocate it in this precise form, but to bring out what scale of change would be possible for a particular form of fee liability.

A more radical, and carefully argued and well-evidenced, rearrangement of fee and grant subsidies has been proposed for Wales by the Diamond Committee. The Welsh Government has accepted the recommendations and recently finished consulting on the detail of implementing it. The change has cross-party support, and support from the NUS Wales and Universities Wales. Anyone interested in this debate should read that report (here), as a further example of the range of possibilities.

What about other objections to fees?

If your objection to fees is that higher education is a public good and therefore students shouldn’t have to contribute on principle, I have bad news. Scotland crossed that ideological bridge a long time ago and is now £500m a year into that territory, because all student loan debt is a form of student contribution, whether it’s for living costs or fees. Moreover, there is no realistic chance that the Scottish Government is going to reduce its reliance on student loans to underwrite the higher education system. £500m is roughly the annual cost of the whole FE system, or 1p on the basic rate of income tax.

A separate objection to fees is that they create a “weakest to the wall” market in higher education. That’s not a necessary effect in the model above, in which the SFC continues to decide where the funded places are, and fully funds the fees of three-quarters of Scottish undergraduate students and half the cost of the rest. It is entirely possible to seek a fee contribution from some students (or even all) in a system as planned as the current one, without moving to a quasi-voucher market.

Another objection is that fees change the nature of higher education, converting what should be a purely educational relationship into a purchase, and positioning students as consumers (some people are for this, but many are not). Around half of students in Scottish universities already pay fees, including many on full-time undergraduate courses (overseas students, rUK students). Many others are already taking out large loans to pay for their living costs. Would asking some, or even all, Scottish undergraduate students to borrow to cover some of the cost of tuition create a dramatic cultural shift from where we already are? That’s debatable at best, I think.

But even if you believe that all the things above would be unavoidable and undesirable, is the price now being paid to avoid them defensible? In order to shelter everyone from any fee at all, we have designed a system which means student debt has to be shouldered disproportionately by those from lower incomes, while people from the most well-off backgrounds are routinely leaving university debt free. It’s the least well-off students bearing most of the cost of these principles.

Investing in grants vs other things

One of the arguments often made for fees is that access to HE remains socially skewed and it would be better, and fairer, to subsidise HE students less and spend more on levels of education which everyone uses. The model above doesn’t address that, because it doesn’t release any cash, it just moves it around between existing students.

The model also therefore doesn’t deal with the relative under-supply of places in Scotland compared to other parts of the UK. A thousand extra places fully funded for fees and grant would cost around £10m. Nor does the model offer universities any additional funding per student: increasing university spending has often (though not always) been behind fee rises.

To deal with these issues as well in any serious way would mean a higher fee, and/or one which was less heavily means-tested, and/or ceasing to provide EU students with free tuition (recalling that none of the sums above included them).

SAAS funds just under 15,000 EU students. The total current spending on them is around £100m a year (15,000 x £7,000: they cannot claim maintenance grant). We don’t know yet what the Scottish Government will decide to do about this group.

In 2010-11, the SG was actively seeking ways to charge these students at least something (here). My assumption is that, once EU law ceases to apply and once the current commitment to the 2017 and 2018 entry cohorts has been met, the SG will return to the issue of how it can reduce its spending on this group in some way, so that some or all of the cash is available for other things. At a time other things are under pressure, the sum at stake simply looks too large at first sight to be affordable as a voluntary symbolic gesture.

Where next?

One of the great campaigning coups of the past 20 years has been the success with which so many people have been persuaded that free tuition is essential to widening access and that defending it must be given absolute priority over improving (or even just protecting) levels of student grant. Thus grants in Scotland were cut by a third in 2013 with the support of NUS Scotland, and no outcry beyond the parliamentary opposition parties. Grants are important too, it is sometimes conceded, but not so important we should give an inch on free tuition to spend more on them. According to this view, the only proper way to increase grants is by finding the cash from some other budget, or more tax, and until that happens it is better to put up with what we have than to raid the fee budget.

I don’t expect any real shift in policy here or even in what people are prepared to debate. The SNP, the Scottish Greens, Scottish Labour and the Liberal Democrats all supported free tuition in the 2016 Holyrood elections (though at least the Conservatives, Labour and Liberal Democrats also mentioned increasing means-tested grants, and the SNP said it would “work to improve” them). The Conservative offering on fees was much more cautious than the model above, limited to something like the old graduate endowment, and would have raised a relatively small amount, and not for several years.

The appearance of any proposal like the one discussed here tends to trigger Spanish Inquisition-like questioning of Scottish opposition politicians about whether they will rule out tuition fees (grants don’t get a look in), with a moment’s hesitancy being taken as political death. This – for the avoidance of doubt – is an absolutely brilliant state of affairs for people whose parents can fund them through university but much worse news for people whose parents can’t.

This positioning of tuition fees as a box which must never be opened even a crack benefits one section of society. It’s the one I know best, and it has always been good at identifying high-minded arguments in defence of its own interests. But rarely so successful as in this case at persuading other people that they must leave their barricade neglected, and come and defend its one instead. It’s been a rather one-sided vision of solidarity so far.

But here we are. The maths of a more even sharing debt among students in Scotland is really pretty easy. The politics look as impossible as ever.

Footnote 1: Living costs don’t matter as much as fees because …

Students can live at home: (a) no, they can’t all do that, (b) even for those who can, it will not always be a particularly good idea and (c) even when it’s a good option, those students still need to be fed, to travel (especially, often, travel) and to have clothes, books and so on, and it’s not reasonable to expect families on low incomes to absorb these costs unaided.

Also, that students can work is not a killer argument against the equal importance of living cost support. There’s a growing literature on the impact of working, especially in term-time. It’s not all discouraging: some types of working, at some level, for some people, appear to be fine. But the overwhelming message is that those students who don’t take on paid employment, especially in term, will tend to get more out of higher education, academically and in other ways.

But there’s a more fundamental problem with saying that fee loans are a problem, but maintenance loans aren’t, because people can work. It confuses the income and expenditure sides of the equation. Logically, you might as well say fee loans wouldn’t be an issue, given a high enough level of grant, because people could work to pay their fees. Unless you accept the second of these arguments, you can’t use the first.

Footnote 2: Actual upfront fees – the 1998 reforms

In 1998, the UK government introduced an upfront yearly fee of £1,000. It was means-tested (this is generally forgotten), so that – roughly – the top third by income paid the whole amount, the middle third some of it, and the lowest third by income, nothing. The dedicated fee loan had not yet been invented (though living cost loans were boosted with the idea people might choose to use some of the extra amount borrowed to cover the cost). The change was very unpopular with those who had to pay, and the way it was discussed obscured that many paid nothing or only part. It was also accompanied by the abolition of grants, but that attracted much less fuss, as did their reintroduction in 2004.

The 1999 Scottish elections were dominated by 1998 fee regime and the sense that fees must be an immediate cost to families persists in Scotland still. However, when fees ceased to be means-tested in 2006, the UK government also enabled them to be deferred using a government subsidised loan. In passing, this means that nowhere in the UK since 1962 have first-time full-time low-income students been expected to find the cost of an upfront fee with no form of government help. But you could be forgiven for not knowing that, from the political rhetoric.

Footnote 3: Debt effects in England

Researchers looking at the statistics, and interviewing students, have discovered a high degree of willingness (not necesssarily enthusiasm, just willingness) to borrow among young students of all backgrounds in England. Participation rates there, including for those from disadvantaged backgrounds, have increased at least as quickly as in Scotland. This is not the same as saying no-one, anywhere has ever been deterred, and there’s more evidence that older, especially part-time, students are more debt averse. But the last 20 years of data from England (and comparisons with Scotland) on participation levels and access have generally not been as helpful to advocates of free tuition as they might have hoped.

This piece, written in late March, considered how governments across the UK might respond to the sudden loss of earned income many students would be facing. It argued that for some students additional earnings are an essential part of making ends meet and that one quick response would be to increase maintenace loan entitlements, particularly for those not already entitled to the highest levels of support, with decisions about how to treat those loans long-term left for later. I said, “I’d be surprised if people in government and higher education across the UK are not already looking at action in this area”.

A month on, what action has there been?

Reducing students’ costs

This is an equation with two sides. Students not being asked to pay rent for accommodation they are not using is the main obvious reason the crisis might cause their costs to come down.

Action here appears to have been patchy. Rent waivers for university-owned accommodation look pretty widespread, although sometimes on condition of leaving almost immediately, which not all students affected may have found easy to manage. Some of the large commerical providers, such as Unite, also made early decisions to release students from contracts. Not all mass private providers have, however, nor all individual private landlords (see this story from Northern Ireland, for example). There has been one survey (I’m not quickly finding the link but will add it if I can later) which appeared to confirm that students were far from guaranteed rent reductions.

Students living at home already were not in a position to benefit from rent waivers, and some may be in households where the collective income has suffered more generally and the pressure to contribute will feel greater than before. These students are likely to be saving more than others on transport costs, especially where refunds on season tickets are available (as in the Greater Glasgow area), but as in the case of Glasgow, these refunds may take a while to arrive.

Part-time students will have been particularly vulnerable to sudden income loss, although they are also more likely to be in more permanent forms of employment covered by some sort of emergency income protection.

Income

On the income side, responses have varied across the four nations.

In England, the Student Loans Company site has posted this Q&A. The message is reassurance of business as usual, with some compassionate concessions on administrative points. If the household income on which support was originally calculated has suddenly dropped this year, the 2019-20 entitlement can be recalculated, as current rules allow, but not immediately, also following current rules. The only clear change in immediate practice or policy appears to be that students overpaid in previous periods will not be pursued for now for repayments.

Welsh students are offered a very similar set of Q&A, as are those from Northern Ireland.

The Scottish Government appears to be the only one so far which has released any additional cash: what is described here as a “£5 million package of emergency financial support”. The detailed notes describe this as made up of £2m for further education and £2.2m for higher education, in addition to a previous £0.569m for HE (implying a total amount £4.769m). The £5m (the figure widely used by others: on the SAAS website, in the NUS press release welcoming the announcement here and in press reporting) therefore looks at first sight to involve some rounding up, by £0.231m (4.8%), unless there is a further reserve whose placing is still undecided. The HE component is to be disbursed by HE institutions as part of their hardship funds.

The SG announcement is a positive move (though it would be better for trust in government if it had been subject to less gung-ho rounding) and intelligently takes advantage of hardship funds as a rapid route for dispensing cash. But it will not stretch far. There are around 120,00 students in full-time undergraduate HE supported by the Scottish Government (£4.79m/120,000=£23), plus many more part-time and post-graduate ones, and ones from outside Scotland but who have had to stay here, all of whom could in theory have a call on hardship funds.

According to The Guardian today NUS president Zamzam Ibrahim has “called on the government to set up a £60m student hardship fund to help support those who are struggling financially.” This would suggest extra support in England on a similar level to what has been offered in Scotland.

It is not clear if there is any appetite across the UK for a larger scheme, and what support there would be for one based on releasing additional loan, or what sort of take up such a scheme might have. Outwardly at least the authorities appear to be relying for now on the loss of earned income for students not giving rise to immediate critical hardship on a scale that requires major action. That feels optimistic. The Guardian also reports that “An NUS survey of 10,000 higher and further education students across the UK … found that up to 85% of working students say they will need additional financial support because they have lost their jobs as a result of the pandemic and subsequent lockdown.”

Even if access to additional loan could not be made available very quickly, an announcement of loan extensions coming in a couple of months might still help. Many students rely heavily on earnings over the summer, a period student funding is already not designed to cover. Full-time students are not eligible for unemployment benefits.

Of course, there will be students who have picked up extra shifts in supermarkets, for example, but the loss of opportunities in the hospitality and leisure industries is going to hit hard. My instinct remains that a more systematic, structural response is going to be needed to avoid many students facing serious hardship up to and including to the point where they may have to drop out, simply in order to obtain benefits. Only the Welsh system, which offers all students the maximum amount for living costs, has some in-built insulation, and even that may not be enough.

Zamzam Ibrahim is reported as believing that “students were in danger of being overlooked”. At the moment that looks a reasonable worry. I still hope people are looking at the more substantial options for intervention here.

Footnote

While student support has not received much obvious attention, the large financial risks to universities have been widely discussed, with talks reported already to be underway between universities and governments in different parts of the UK. The central issue, massive anticipated losses in income, particularly due to a large fall in overseas students, has been well-covered across the media. The Wonkhe website is a good place to look for lots of thought-provoking pieces on what HE faces and how it might need to respond. Alex Usher in Canada has been pressing for institutions to grasp the full implications of students being unable to return to campus in any number until at least January.

Some of this debate applies UK wide, but by no means all. The debate in England about tighter management of unconditional offers, and fears that some universities will scoop the pool to the detriment of others, to fill missing overseas student places, does not resonate in Scotland, where de facto number controls on recruitment by each institution persist.

While the loss of overseas students affects all parts of the UK, as HEPI research showed in 2017, backed by more recent work by Audit Scotland, Scottish HEIs are unlike those in England in relying on cross-subsidy from overseas students to prop up domestic teaching costs, which are not fully covered by the funding the Scottish Government provides direct to universities for the teaching of Scottish undergraduates. Scottish universities which have fewer overseas students as a proportion of their intake were already living closer to this problem than those with more: but it now becomes a clear sector-wide issue. As argued here (in 2015, this is a long-standing point) despite the rhetoric about differences in HE systems across the UK, participation in the market for overseas students is a central part of Scottish Government HE strategy, for financial as well as soft diplomacy reasons.

Whether Scotland will see a drop in students from the rest of the UK is also something to think about: we are a net importer of such students, who make up around 10% of UK undergraduates here. System-wide, these students will also bring in more funding per head than Scots, though less than overseas ones. They will provide a marginal income gain but, more importantly, simply by coming here they help to sustain the sector at its present size. If students are rattling round an emptier the English system, fewer may wish to come to Scotland. The psychology of the pre-vaccine COVID era, with increased risk of sudden lock downs, may also encourage people to stay closer to home, at least for a while. We don’t know yet what will happen there, but it’s an additional exposure Scottish universities face.

As a further obvious point, while universities everywhere in the UK are now pitching for support in a context of massively increased demands on public funds but reduced tax income, Scottish ones do it from a position where their core teaching budget is already part of that competition, in contrast to other parts of the UK, particularly England and Wales. So what is given with one hand is at greater risk of being taken away by another.

Lastly, although Scotland may get its Barnett share of any rescue package devised by the UK government for institutions in England, we have a larger university sector than England, proportionate to population size. So any funds coming north will have to be spread thinner. (Conversely just for once Northen Ireland will see some benefit from being substantially under-provided.) On the other hand, the Scottish Government was on the cusp of an HE-related windfall, with EU students falling out of free tuition, which would have been expected to release around £90m over the next 4 years. The debate about what to do with that money will presumably just have taken something of a swerve.

As a policy response to all this, there still seems as yet no political appetite in Scotland for providing a new source of income for institutions by introducing loan-backed tuition fee contributions of any size, for any group of domestic undergraduates. This is despite the Scottish Government having never used anything like its full share of the student loan pot: several hundred million pounds should in theory therefore be there for easy taking, were fees introduced (the only way this could realistically be accessed: more here https://twitter.com/LucyHunterB/status/1248593756884029440?s=20). There are signs today that university leaders are beginning to challenge the assumption that this policy cannot be discussed: see here.

The lead time for introducing any policy change on fees would be at last a year. An election for Holyrood is scheduled for 2021 (already a year later it should have been). It is hard to imagine a more acute test than the current choices facing politicians of how far free tuition remains an existential policy for the SNP, which must surely anticipate it will remain the largest party, how far other parties continue to regard the issue as untouchable and how far questioning voices in the sector are prepared to challenge the existing policy.

Shortening how long students spend obtaining a degree (most often expressed as the four year degree debate in Scotland, but other versions of this argument are available) does not yet appear to be under discussion. Indeed, there is potential for serious Government-institution tension over degree length. The last thing the universities will want right now is a reduction in how many years the students they do still have are funded to spend with them, while the government has never been more incentivised to bring down the cost of producing graduates. I’ve seen one suggestion that the logic of sticking with free tuition would be (in effect) nationalising the universities, so at least they cannot technically go bankrupt: while that would be radical in constitutional terms, it would not address the fundamental balance sheet problems.

I wonder if one other issue which might be on someone’s radar is that a drop in non-Scots would be an opportunity to reverse Scotland’s lower acceptance rates for domestic applicants over the past decade. However, while that would deal with a detriment experienced by recent and current cohorts of Scottish applicants, in the absence of any change to fee policy, it is only helpful to universities if accompanied by further fee income from the government cash budget, taking us back to square one; and the knock-on effects of letting more students into university would be likely to be a drop in the take up of short-cycle HN courses in colleges, passing on some of the unversities’ problems to that tier of the system.

Substantial changes may well be needed to traditional HE systems in many jurisdictions, in response not just to immediate pressures but the longer term consequences of current events, and, like any country, Scotland will have its own particular issues there. But short-term institutional financial survival is what appears to be weighing most heavily on people’s minds across the UK right now, unsurprisingly enough. And this perhaps also explains why addressing immediate pressure on student incomes remains, I think, an area of unfinished business.

Meet Mike. Mike swims like a fish.¹

Public information films were a constant of my 1970s childhood. Some I can still quote (see above). With others what wasn’t said or shown left the greater impression: if you too grew up in a farming area in this period decades later you may still recoil at the words “slurry pit”, even if you have never seen one.

In the discussion of what happens over the rest of this year, there is much talk about how and when people will be allowed greater freedoms. Perhaps schools will re-open before other things, or masks may be compulsory. The focus is on the content of policy to come.

Since the start of offical restrictions, I have done all our food shopping, applying a calculation that the other adult in the house is older and male and therefore more at risk. Without exception, these trips to the supermarket have required ninja skills to avoid being within one metre, let alone two, of anyone else no more than once every few minutes. Whatever I had done, other than walk out of the shop (which I have, once) it would have been impossible to get well down the shopping list without multiple close encounters of the unchosen kind.

Having now found a time and place which seems to be predictably very quiet, last time out I still reckon that I had to swerve, reverse or (with no space to move) just put up with someone coming within a few feet between 10 and 20 times over perhaps 20-25 minutes. That excludes the aisles I didn’t go down because someone was standing right in the middle having a long think. It’s true that one man and his son were giving a good demonstration of Brownian motion wherever they happened to be, but they were not alone. My rough calculation is that up to a third of people were somewhere between largely oblivious and possibly even (just going by demeanour) resentful of physical distancing rules.

I’ve seen a lot of praise from government for how well people are observing the “stay at home” message. It’s less clear, not just from my own experience but from what I see on social media, that the message that how you behave while you are out can be equally life-saving has sunk in equally well. I could at this point mention the footage from Westminster Bridge last week.

Yet whenever and however restrictions are loosened, how well physical distancing is observed looks likely to be critical to how far and how long allowing people more freedom of movement can be sustained without provoking a further spike in infection and potential re-tightening of the rules, and along the way avoidable deaths.

The time to get people absorbing a message about keeping their distance and acquiring new habits is not when any rules are loosened, but now, before they are. Perhaps government has its own intelligence suggesting these rules are better understood and observed than assumed here. Perhaps Cameron Toll and Straiton in Edinburgh are particular hotbeds of distance-denial. I am doubtful, though.

When the time comes we will not always be able observe a 2m distance. Our pavements are too narrow, and as roads get busier, walking in the road will become much more dangerous (of course, there is also a movement for temporary road closures). Our buildings are not routinely designed with such wide corridors. But risk management is about risk reduction, not risk elimination. Wherever there is space, it needs to be used and where there isn’t, people still need to do what they can. But this will not work if more than a very small proportion of people do not join in: it does not take many free spirits to crash through everyone else’s efforts here.

The law is not much use for this, I think. A regulation requiring a blanket 2m distance would be hugely impractical, even if we were all issued with giant crinolines. Put in caveats about “where possible” and it becomes hard to enforce. Perhaps some obligation could be placed on employers to make reasonable arrangements for distancing their staff. But for the general population out and about what is needed is a new Mike.

The public information message has been very strong on #StayHome. But we also need #KeepBack (or whatever) and we need that well before any rules are loosened, emphatically and inescapably. Governments need to research urgently what is going on with the people who seem to be finding this hardest to do, whether they fit any particular demographic, and target them hard. Maybe many of the people who seem to me to be radiating a low level sense of fury at any disruption to their normality are in fact just scared or preoccupied. Maybe others think they are doing the right thing and just have no idea what these distances mean. I wonder about any public message involving any figure, even just “2”, in a world where a distressing number of people appear actively frightened of numbers.

We have a whole advertising industry which exists to do behavioural influencing, employing very clever people. If loosening the current rules is accompanied by a minority of people grasping with relief the chance to behave as though everything is completely back to normal, we are likely to spend longer in cycles of release and restrict, and the overall economic hit is likely to be harder. It is in the interest of the advertising industry to put its talent at the service of avoiding this.

However and whenever things change, learning to keep our distance from each other as much as possible outside our own homes is going to be part of the making this work as well as it can and a necessary part of how we live perhaps for quite a long time to come. It will save lives. Perhaps more vulnerable people will not need to be so restricted for so long. Like handwashing, this is an issue for public education, not law, and the time for that is as soon as possible. If the achievement of physical distancing is left to current levels of public information, whenever the rules are loosened, I reckon my current ninja supermarket shopping will feel like a walk in a heavily-policed park by comparison. Unless they know for sure that what’s evident in south Edinburgh is exceptional, it looks as though governments need to get to work on influencing our behaviour harder on this now, to monitor it, and to take into account how well we are doing in deciding what to do and when. On this, we will sink or swim together.

¹ It’s very 70s. You have been warned. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v9FsEi2us88

Many students depend heavily on part-time work to make up their income, in the sort of sectors which will be most heavily hit right now. Fortunately, many of them are also already within a form of welfare (though we don’t often think of it as that) through the student finance system. This post suggests some quick decisions which could be made about student finance to help deal with lost income. It looks just at those who are on the main student support package, so excludes those on special packages, which includes nursing and midwifery students in the devolved nations. Their situation is likely to become a separate debate.

A quick search just now doesn’t bring up any announcements on student funding in any part of the UK yet, but that could change quickly. I’d be surprised if people in government and higher education across the UK are not already looking at action in this area.

This post looks particularly at Scotland and Wales, but similar arguments apply for England and Northern Ireland.

Cutting costs

What’s happening on the other side of the equation from income obviously matters. The largest outgoing for those away from home is rent, paid to universities, individual private landlords and, more and more, mass private providers of student accommodation. Rent holidays would be the largest single thing that would take the financial pressure off the student population. So whatever is being done to make those a reality needs to take in student accommodation, and students as private renters. For specialist mass providers, universities and private, allowing contracts to be ended early would also help, and any help with covering the cost to providers of doing that should be looked at as another form of call on the budget for rent support.

Mortgage holidays will affect fewer students directly, but will be relevant to some mature students, particularly, and ought to feed through into suspended rent payments, in some cases.

Commuting students will see their costs fall – but not if they are locked into annual passes. So they will have an interest in anything being done to write off unused travel pass periods.

Substituting for lost work

Action on rent will take off much of the pressure, but the student body is very variable in its needs and some flexibility on the income side will also make sense. Not all students live away from home, and students who live at home use part-time work to deal with financial pressures too.

In Wales, every student living away from home is already entitled to £9,225 of support through a combination of loan and grant (£8,100 grant at lowest incomes, tapering to minimum universal £1,000 regardless of income). For those living at home, it is £7,840 (and those in London £11,530). Details are here. Particularly if there is quick action on rents, the Welsh system already provides a form of universal income that might be enough as it stands, as long as people can apply late for support they had not expected to use.

Total living cost support in other parts of the UK declines as family income rises, and is lower, and there is a more obvious case for intervention.

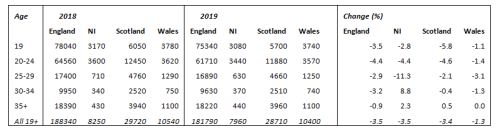

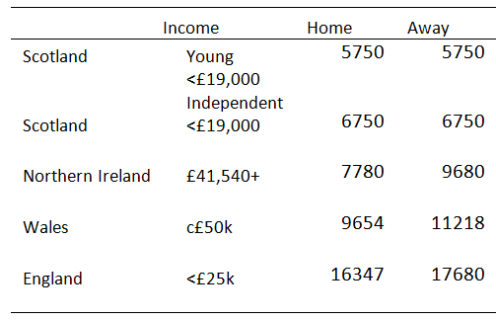

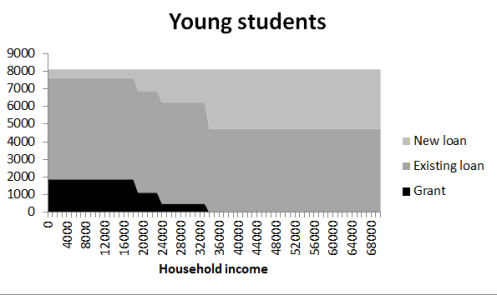

In Scotland at the moment the situation for full-time undergraduates is what’s shown below (young students top, mature students bottom). The sums are the same wherever students live or study.

I am worried particularly about those people on the £4,750 package who already didn’t have easy access to parental support (£34,000 is not a high household income), and who are very likely to be relying substantially on part-time working.

There is no way the Scottish Government outlay on student loans in the current or next financial year is going to be its pro rata share of outlay in England, so getting Treasury permission to turn on the loan tap more should be open to it as a quick way of easing cash flow pressures on students. Whether additional borrowing provided this way can be commuted to grant, or else written off, would be a decision for later. There would be choices to be made about how much extra loan, and who for, but at minumum lifting the maximum loan for people in the lowest support category looks easily justified.

Changes in parental circumstances

There will also be students whose parents suddenly cannot provide as much help as they did before. An emergency loan extension facility, which again might later be commuted or written off, would be an immediate help for that group also.

Administration

The main practical issue is likely to be having people available to process applications and issue loans, at SAAS and the SLC. That argues for doing things that are as simple as possible in form.

Institutional support

Hardship funds and institutional bursaries are an existing safety valve. But the scale of the call and pressure on administrative staff is likely to limit what can be done with those.

Overview

In Scotland, all these things point to a case for some form of emergency extension of the student loan scheme, which might be as simple as a flat-rate additional borrowing extension to everyone, with the ability to turn round applications quickly the main challenge, particularly for those who are not already borrowers.

Regular readers of this blog will know I am an advocate of student grants. But the reality of the scale of the cash call on government budgets right now means that in this one area where there is an established loan scheme, it offers an additional way of addressing immediate financial hardship, whatever later decisions are taken about what to do about such additional debts. The main argument against relying just on this looks to be how quickly national bodies can process applications, compared to institutions, who will tend to have more facility to move quickly.

Northern Irish students are also on a very restricted level of living cost support, and will face similar pressure on lost work. For English students, living cost support is generally higher than in Scotland or Northern Ireland, but below that for Wales, and England has the same tapering that will catch out students whose family income suddenly drops, or who were already heavily reliant on part-time work to fill the gap left by the state.

In these strange times, student finance may look like a minor issue. But not for those who rely on it. Rent holidays and shortened tenancies will help this group, but the potential for using the student loan system as a source of short-term relief deserves attention too.

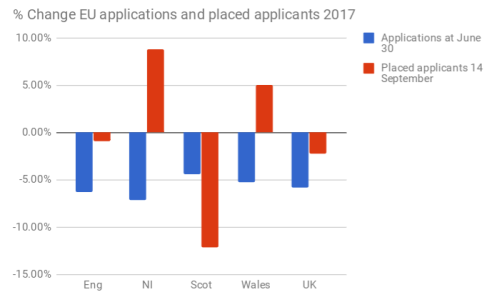

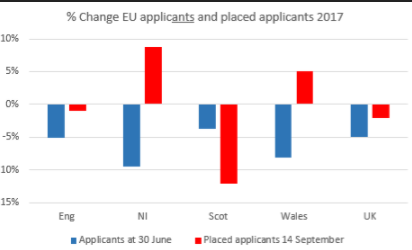

The latest UCAS applications data got some coverage last week highlighting differences in trends between Scotland and other parts of the UK (for example https://www.scotsman.com/education/university-applications-by-18-year-olds-dip-slightly-in-scotland-1-4963636). There was an argument over whether the sharper rise in those from the most deprived areas in England (+6%) than Scotland (+3%) meant anything and what the relevance was of the higher numbers in Scotland who do an HN qualification at college without passing through UCAS, before going on to university.

These figures look at the demand for places, not who gets in. What do they show?

Cross-UK comparisons in general

Over the years, people (including the SG, which this week was arguing comparisons cannot be made) have used cross-UK comparisons of UCAS numbers to claim certain things are proved about HE policy, specifically decisions on student funding. Cross-UK comparisons are tricky: but they are not impossible, for the reasons discussed here https://wonkhe.com/blogs/comment-scottish-english-access-must-be-compared/ .

Number of 18 year olds applying

I don’t like comparing this, because there is no control for underlying year-on-year variation in the size of the age 18 population. So I won’t.

Age 18 application rate

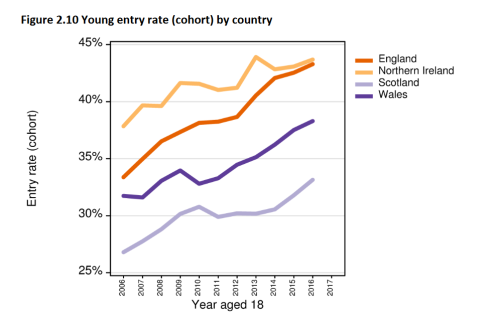

This is a much more useful thing to compare, because it controls for fluctuations in the number of 18 year olds in each nation.

Comparing the absolute values still hits the college-level HE problem: there are people who will eventually go on to university in Scotland who are missing from these numbers.

The trend over time is the thing to focus on. It gives a decent comparable measure of how the proportion of young people interested in going straight to university from school has changed. The way age is measured by UCAS takes into account that school leavers tend to be a bit younger in Scotland (so there are relatively few under 18s in the Scottish data).

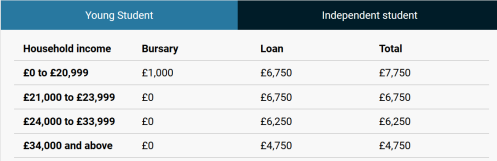

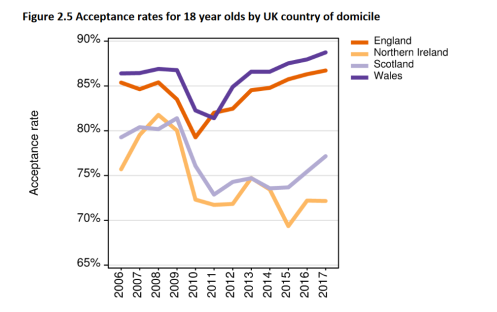

The most recent age 18 application rate figures from UCAS look like this:

Beware: the y (vertical) axis doesn’t start at zero, so this graph at first glance exagerates relative change over time.

Even so, it’s a pretty clear story of a flat line in levels of interest in Scotland and Wales, and a slight drop in Northern Ireland, since 2016, but a steady increase in England since 2016 (and longer, but 2016 is where the divergence becomes clear).

We cannot tell how far the proportion of 18 year olds applying to college in Scotland has risen or fallen over the period (no data is collected centrally on college applicants), so the invisible Scottish line which includes all applicants to any kind of HE could either have risen or fallen over the period. All we can tell is that applications for direct entry to university in particular have remained static.

If you were inclined to think that any specific detail of funding systems has less impact than is often asserted on whether school leavers will apply to university, this would be Exhibit A. Whether you were to look at total fee debt, total debt (including for living costs), the value of grant, the upfront value of all forms of living cost support (loan plus grant) or changes to the repayment terms for loans, you would struggle to find an explanation in policy variation across the UK over time for the differences between these lines.

Why the application rate for students in England has risen so consistently and unusually, even as the amount of debt involved has grown, is an obvious question. We don’t have the age 18 entry rate by region within England: the absolute numbers suggest there could be substantial variation in that, and exposing that might help isolate non-funding factors (exam results? the economy?).

Of course, effects from one or more funding changes could be being off-set by other factors. But if that thought were to be combined with the common belief that high fee/high debt systems are generally bad for demand from young people, you’d need to ask what was going in England which means the increase would have been even greater, if different funding rules had been in place.

None of this tells you what student funding policy should be, or that funding is completely irrelevant, but it does suggest simple causal arguments about the relationship between funding, particularly individual elements of that, and demand from school leavers should be avoided.

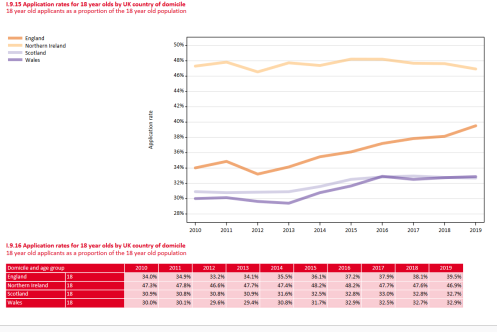

Applicants aged 19 and over

It’s harder to control for demographics once you look across other ages. The way the numbers are provided means extracting this is is fiddly, so this table only compares 2019 with 2018.

The number of applicants aged 19 and over has fallen in every UK nation: by around 3.5% England, Northern Ireland and Scotland, and by 1.3% in Wales. The number of 18 year olds has been falling for a while, so the drop in 19 year olds and 20-24 year olds is likely to explained in part by that. That Wales has not seen such a fall in under 25s might be due to less acute demographic change: but if it is not that, the recent changes to student funding there might be relevant. There have been some signs from other data that older students are more sensitive to changes in funding regimes. But then Wales doesn’t have a clear advantage in students over 24, so that’s not an argument that I’d want to push too far.

The particularly large drop in 19 year old applicants in Scotland again could be down to differences in demographics. If not, it’s a bit puzzling, not least as any increased use of UCAS to record college to university moves, as has lately been encouraged, would be expected if anything to cushion the figures for that group.

Students from disadvantaged backgrounds

This year, for the first time (I think) UCAS has published figures based on the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) produced for each nation. Each IMD is different in its detailed construction, but they all measure multiple disadvantages at the level of small areas, rank these areas and then group them into 5 bands (quintiles), from the most to least disadvantaged. Quintile 1 covers the 20% of most disadvantaged areas. The figures here are still not strictly comparable between nations but they ought to be better than previous cross-UK measures for comparing by area type. The SG’s long-standing line, used again this week, that UCAS’s measures of disadvantage in different nations are comparing different things now feels a bit out of date.

Area measures do not tell us directly about individual disadvantage and it could still be that the relationship between area and individual disadvantage varies by nations (perhaps low income people are more concentrated in multiple disadvantage areas in one nation compared to another, for example).

Still, area disadvantage in the Scottish Government’s benchmark for success in widening access so it is not off the wall to compare these numbers.

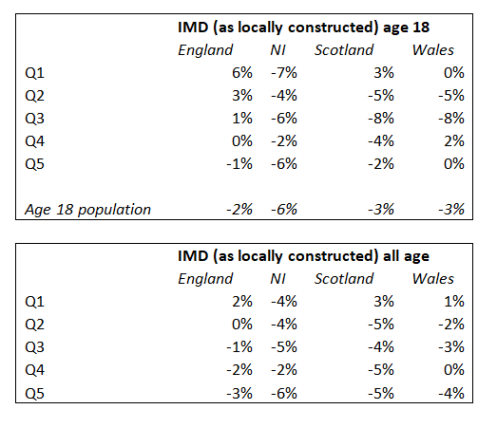

The percentage change for 18 year olds and for all applicants in each nation by IMD quintile is shown below, along with the overall change in the age 18 population, for context.

The press association story linked above compared the +6% in Q1 in England for 18 year olds with the +3% in Scotland. The age 18 population has dropped a bit more here, but not enough to explain the gap.

It’s imperfect, but I think it’s reasonable to say that over the last year applications from school leavers direct to university from the most disadvantaged 20% of areas have risen faster in England than Scotland. Wales and Northern Ireland both look less good again. Scotland has a particualrly sharp cliff-edge between Q1 and the rest. This may reflect the recent intense policy focus on Q1 in Scotland.

Across all ages, things look better for Scotland compared to England in IMD Q1, though less good outside those areas, including in Q2. Again the cliff edge between Q1 and the rest is much sharper in Scotland.

A wider point is that single year comparisons are generally less revealing than those looking over a longer period, so a further piece of work could use the IMD figures going back further, and control for changes in the number of 18 year olds over a longer time.

Conclusion

UCAS is the nearest thing we have to a measure for demand for university places. With the move to publishing IMD figures for every nation, our abilty to compare groups of applicants by area type, at least, has improved. An application rate at 18 for each IMD quintile in each nation would be even better, because that would remove any remaining demographic effects.

Even allowing for all the limitations, these figures show that:

- over recent years demand from school leavers has grown faster in England than in other parts of the UK;

- in the past year at least demand from school leavers has grown faster in the 20% of most disadvantaged areas in England than in Scotland (and Wales and Northern Ireland are both further behind);

- the fall in applicants aged 19+ over the past year is negligibly different between England, Northern Ireland and Scotland, but Wales fell less; and

- in the past year Scotland saw faster growth, relative to the other nations, for applicants in total, of all ages, from the most disadvantaged 20% of areas, although both for 18 year olds and all ages the cliff edge in the year-on-year change between Q1 and other area types was especially sharp in Scotland.

Comparing IMD figures over several years would reveal more.

UCAS numbers remain a dubious basis for making claims about the inherent superiority or inferiority of any nation’s student funding system. Still, something has stimulated faster growth in demand from school leavers, specifically, including those from the most disadvantaged areas, in England since 2016. What that might be, however, is a whole other question.

Note on data

All data available here: https://www.ucas.com/data-and-analysis/undergraduate-statistics-and-reports/ucas-undergraduate-releases/applicant-releases-2019-cycle/2019-cycle-applicant-figures-30-june-deadline

Change in the total number of 18 year olds in each nation extrapolated from the application rate and absolute numbers in 2018 and 2019.

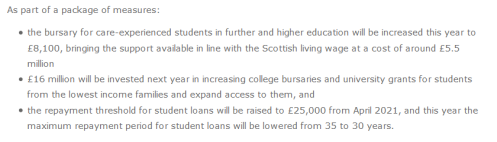

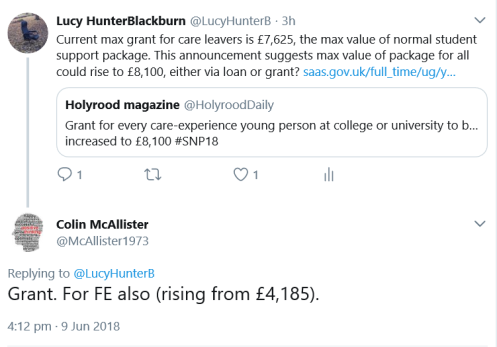

An announcement is expected soon on living cost support for students in Scotland, expanding on a few things made public this weekend. This looks likely to be the formal response to last year’s Scottish Government review of student funding.

This post provides some context for any announcement, by bringing together information for the four UK nations on living cost support for full-time undergraduate students in higher education. Unlike the Diamond review in Wales in 2016, the Scottish review did not make proposals for post-graduate or part-time students, although it did also cover support in FE.

Why make comparisons? Mainly because claims of being “best in the UK” have been used repeatedly to justify developments in Scotland over recent years, and might be expected to be made again. The main message from the material below is that comparisons here are complicated: beware of sweeping claims to “bestness”.

Total value of maintenance support

The analysis below covers support for students studying HE-level courses, whether at college or university.

(i) Away from home

The majority of students from all UK nations live away from the parental home, including those from Scotland. These students will tend to face the highest costs, especially for housing.

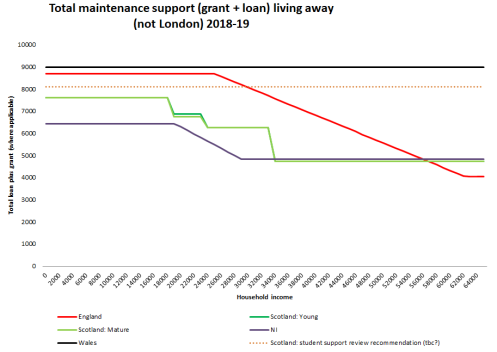

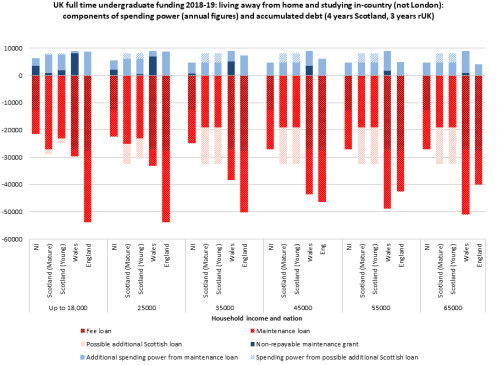

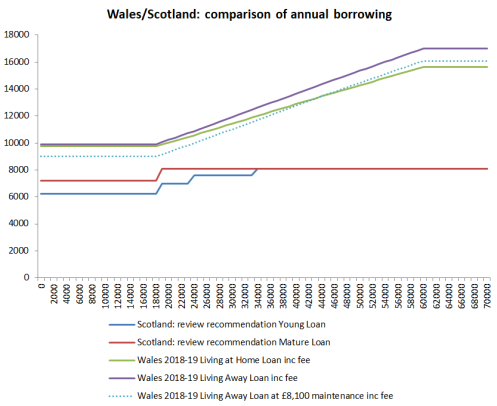

The graph below shows the total value of support, i.e. any grant plus loan, currently on offer for students living away from home in 2018-19 in the different UK nations. Also included (dotted line) is the proposal from the Scottish student support review. The graph shows what students get if they take out their whole loan: different approaches in the UK to loan and grant are looked at in more detail below.

Scotland on current plans sits some way below Wales and England, except at the highest incomes, with a maximum of £7,625. It is above Northern Ireland at incomes below £34,000, and marginally below at higher ones. Generally, families in Scotland are expected to find a lot more upfront help than those in Wales or England, especially once income tips £19,000 and until it reaches over £50,000. The Scottish system is often held up as being distinctive in the UK because it is not based on “ability to pay” (the FM repeated this at the weekend): but if your pre-tax household income is £25,000, your family is currently expected to find some £2,500, or more, a year upfront towards your keep than they would be in some other parts of the UK.

If the Scottish government accepts the review’s recommendation that all students should have access to £8,100, by increasing student loans, and implements it in time for 2018-19, total support will still be higher in Wales, but only in England at incomes up to £29,000. The change would substantially improve the total support offered at lowish-to-middle incomes..

In the nations other than Scotland students get around an additional £2,000 if they study in London and are living away from home (not shown in graph for simplicity), meaning that for students in London, Scotland is the least generous nation.

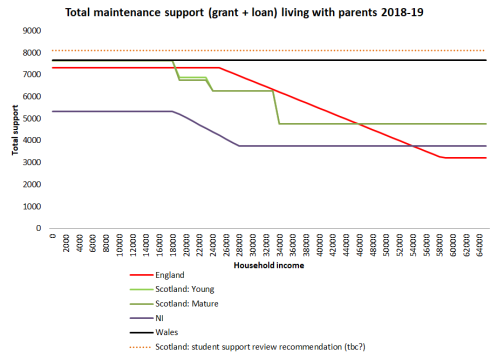

(ii) Living at home

Scotland has a larger minority of students living in the parental home than elsewhere (it is hard to get good data, but the figure looks to be around 45%). In the other UK nations, such students get around £1,500 less than those away from home, but the Scottish system does not make this deduction, so Scotland compares better for this group, sitting just £25 below Wales at incomes below £19,000. It is also above England up to £19,000, but is substantially less generous for some incomes not much above that. It is always better than Northern Ireland.

If the student support review recommendation is accepted, then Scotland will have the highest support in the UK for those living at home. Having the highest combined grant and loan package for this group can only offer a limited basis for claiming “bestness” however, as:

- Much of this support is offered as loan, while these students appear less likely than others to borrow, and may even live at home partly to reduce their borrowing, meaning the notional amount is less likely to be realised in practice. Students living at home who choose only to take their grant will do better in Wales and Northern Ireland (see below).

- Many students do not have the option of living at home.

- It is students who live away from home who face the highest costs.

(iii) Part-time undergraduates

Part-time students in Wales and England will receive a pro rata share of the main living cost package from 2018-19. On current arrangements, this will not be the case in Scotland and the student support review did not include part-time students its costings. So the Scottish government would have to go further than the review recommendations to do anything for this group.

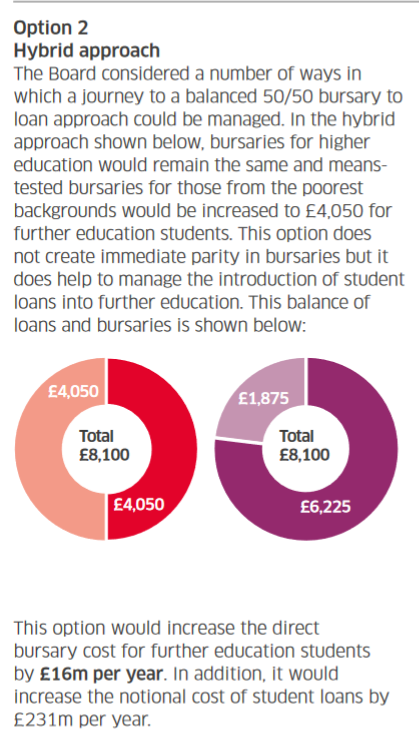

(iv) FE students

Scotland is already providing much more support to this group than other UK nations (I don’t have charts for that: it is evident from a general scan of the situation). Adopting the review proposal to put them onto the total value of support as HE students would reinforce that. However, the review recommends doing this through both an increase in bursary and the introduction of loans into FE. Take up of loans is already lower among HE students in college than in university: it seems likely therefore that take-up among FE students in practice of the new full £8,100 grant and loan package would be limited. The review’s proposed higher maximum grant of £4,050 would however still compare well with other parts of the UK, just by itself.

Overall comparison

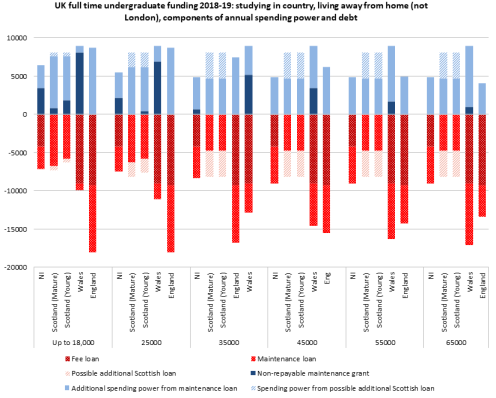

A full comparison of living cost support means looking at the balance of grant and loan, and once loan comes into play, it is misleading not to bring in debt for fees.

The chart below shows how systems compare at various incomes for those living away, but studying in their home nation. For the English and Welsh, crossing a border within the UK makes no substantial difference, but for the Scots and Northern Irish, you have to imagine a £9,250 additional fee charge if they wish or need to do so.

Above the line in blue is the value of upfront living cost support (“spending power”), separated into grant and loan, with the impact of acting on the review recommendation shown as an additional element for Scotland. Below the line in red is the associated debt, separated for fee and living cost loans. The living cost debt mirrors the spending power given by the loan.

(The chart for those living at home would be similar, but takes about £1,500 off the maintenance loan elements above and below the line for the nations other than Scotland.)

The comparison above works best for those on identical length courses, such as one and two year HNs, or degrees which take the same length of time in all parts of the UK. However, an honours degree in Scotland takes 4 years compared to a more typical 3 in the rest of the UK. The chart below is therefore a better comparison for most honours degree students. Above the line it still shows the annual value of living cost support, as this is consumed immediately; but below the line, it now shows accumulated debt over the period of study.

If an extra year of study is factored in, Scotland is already similar to Wales, especially for mature students. At low incomes, these two will be near-identical, in terms of total annual living cost help and accumulated debt, if the Scottish review recommendations are accepted. For mature students at the lowest incomes (which is most mature students), the marginally higher debt in Wales is all due to their great spending power. [Note added: The difference in interest rates while students study is not added in here. Relative to lower interest Scotland/NI, that adds £3-4k for those at incomes up to £35k in Wales, but more for those where gap is already larger, ie with higher borrowing in Wales and England.]

At lower incomes, if you can save a year of study by not being in the Scottish system, Northern Ireland is already the lowest debt nation, reflecting that living cost loans are very limited, as well as fees being lower than in Wales or England. It will be the lowest debt nation on this model at all incomes, if the Scottish review recommendations are implemented, again reflecting its less generous living cost support.

England is always much higher, and Wales joins it as income rises, yet again because it uses loan to offer more living cost support at higher incomes. This chart cannot show:

- how far take-up of loan will vary in practice, especially of living cost loan. Maintenance loan take-up is 85%+ in the rest of the UK, but only about 70% in Scotland, where there is substantial non-borrowing especially among students from higher incomes. How far higher income Welsh students use their new, higher loan will be something to watch.

- the effect of the higher interest used in England and in Wales. In Wales this is partially off-set by a flat-rate write-off of £1,500 as soon as a graduate starts to repay, which will remove some or all of the the effect of higher interest during study, but not later.

- how far headline debt will translate into actual repayments: higher debts are less likely to be repaid in full than lower ones.

The last point is critical, but very hard to predict. Higher interest will further increase the total cost of repayments, in England and in Wales. But write-offs are expected to have most impact on the highest borrowers. Then again, even among the English and Welsh, some people will still feel the full force of their initial borrowing: there will be higher earners who receive no write off, and middle earners who do benefit from a write-off, but mainly or all of accumulated interest.Thus the difference in costs by country actually experienced over time should be less stark on average than shown in the graph, especially for women, who tend to earn less than men, but the variation round the average for students who left HE with similar debt will be very large for England especially.

Is anyone best in the UK?

It really does depends who you are, what you care about, who you regard as equivalent to who, and how you take into account that some of the difference in debt is because students get different levels of benefit in different systems.

Scotland is already best for FE-level students, regardless of any further announcements made this week.

For HE, if your family finds it hard or impossible to support you, Wales’ post-Diamond review package works best, taking the pressure off family contributions across the board. At lower incomes it offers this help almost all in the form – grant – likeliest to be taken up, so that overall debt for this group is similar to that for fee-free Scots, especially mature Scots.

If you are going to be a pretty lower earner who is unlikely to pay back much of your debt (a group which will disproportionately be women), again the Welsh system looks best: generous upfront support at little later cost. However, if the Scottish review is implemented, future low earners who can live with their parents while they study will get most to live on in Scotland.

Similarly, if you are part-time, and cannot contemplate studying without help with living costs, you want to be in Wales or otherwise England, where there’s at least the option of a loan. In both those nations, however, you will need to be willing also to borrow for fees.

On the other hand, if you are full-time, young and from a family who can manage to cover much of your living costs in cash and kind, and want to and can get a place in Scotland, Scotland offers the best deal, with the option even of emerging debt-free. Don’t be a Scot who wants to study in London, though: they get an unusually raw deal of relatively poor living cost help plus fees. The Scottish system is generally poor for border crossers, as is the Northern Irish one: both are high debt, for limited upfront help.